[The following report was issued by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations in June 2012.]

Syria: Joint Rapid Food Security Needs Assessment

Summary of Findings

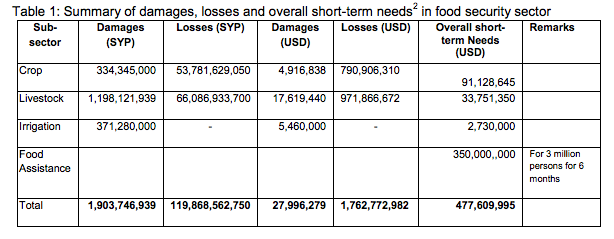

Crops and livestock sectors are the most affected by the ongoing crisis in the country. Table 1 summarizes the total damages and losses in the nine governorates in the crop, irrigation and livestock subsectors.

Majorly affected crops are the strategic crops, such as wheat and barley; fruit and other trees (cherry, olive, other fruits, ornamental trees) and vegetables in the nine governorates. Rise in fuel costs and unavailability of labor force have forced the farmers either to abandon farming or leave the standing crops unattended. Migrant labors, mainly from the northeastern and eastern parts of the country, have left the agriculture producing areas due to insecurity, which has caused a severe shortage of labor. Labor wages have gone up sharply and the farmers are not able to hire the required number of labors due to lack of money. Harvesting of wheat has been delayed in Daará, Rural Damascus, Homs and Hama due to lack of labor and reluctance of the machineries owners to rent out their machineries due to insecurity, and hundreds of hectares of wheat are not harvested. There is thus a great risk of losing part of the crop if there is further delay. At the same time, the livelihood of the "returnee" migrant labors in their places of origin is at serious threat due to lack of employment opportunities, and fast depletion of their resources. Selling of assets has become common among the most vulnerable in all the governorates as an immediate coping strategy. Insecurity has caused restriction in movements of farmers and extension workers that has seriously hampered the agriculture related activities. Pest and insect attacks are not properly addressed. Farmers are turning back to the forest for firewood due to the unavailability of cooking gas and fuel, and deforestation is on the rise.

Irrigation is affected as the electric pumps are not operating at their full capacity due to lack of diesel and high prices. Frequent electricity cuts do not allow pump operation at full capacity, which eventually affects the crops and the fruit trees. In irrigated areas, some channels have been clogged and damaged due to lack of labor and inaccessibility. Lack of fuel and electricity cuts have affected water supply and distribution of water in the fields, which created chaos and social tension among the farmers. Canals in some areas have been reported breached by the farmers due to unavailability of sufficient irrigation water.

The livestock sector has been affected to a greater extent. The hike in fuel, fodder and concentrated feed prices has forced the herders and small families to sell a part of their flock at reduced price to meet their growing expenditures. Herders reported to have some of their livestock killed or stolen during the crisis. Insecurity has hindered the movement of animal health workers from the governorate capitals to the villages, preventing proper animal health service from being provided. No outbreak of any animal disease, however, has been reported so far. Insecurity has also hindered the movement of livestock for grazing, especially in the grazing land zones 1, 2, 3, and 4, in particular in Homs, Idleb and Hama. The Bedouins from Al Badia are moving to northern and northeastern provinces putting more pressure on the pastures there. Furthermore, due to the prolonged drought in zone 5, Bedouins in Al Badia also reported that the livestock reproduction rate has been affected.

The poultry sector has been severely affected by the ongoing crisis. Imports of mother chicks from abroad for the production of one-day chicks in the country are hampered due to import restrictions. Lack of fuel, load shedding and rises in poultry feed prices has nearly doubled the production costs of eggs and chicks. In the meantime, major chicken producing farms in Homs, Hamah and Idleb have been closed, making the supply of poultry meat lower than the demand, and the price has significantly increased in the local markets. Many of the poultry farms producing chicks have stopped their operations, in particular in Rural Damascus, which supplies one-day old chicks, and the running farms have reduced their capacities by almost half. Workers, who mostly hailed from the northeastern and eastern part of the country, have been laid off. The ones currently operating at reduced capacity with resident labor families are taking losses, but are hopeful that the situation will normalize and their business will pick up.

The inland fishery subsector, which provides protein as well as cash income to the local communities, was affected to some extent by the crisis. Details of the damages and losses in fisheries, however, could not be obtained.

The Department of Agriculture in different governorates reported to have lost vehicles, farm machinery and some heavy equipment. Some of the extension service facilities in the areas have been burned and robbed. The extension and animal health workers are also reported to not be in a position to travel to rural areas to support the farmers and herders due to growing insecurity. Forest monitors are unable to monitor their works, and deforestation is reported to be on the rise, as people are going to the forest to collect firewood thanks to rising fuel costs.

In general, the depreciation of the Syrian Pound (SYP) has been a severe blow to the purchasing power of Syrian citizens. Inflation has dramatically risen and the food prices have drastically gone up, and the prices of milk, meat and chicken have gone to as high as three hundred percent in certain places. Though the rural population is able to get some food items from the local traders, the credit limit they are allowed is two thousand Syrian pounds for a maximum of two weeks. Since the rural traders are also small ones, it is difficult for the vulnerable people to ask for food and other commodities on credit for long periods of time. Thanks to the support provided by the government, local bakeries are functioning and bread is still available in required quantities for about nine Syrian pounds per kilogram; however, lack of gas and fuel is slowly putting pressure on the supply of bread as well. In some directly crisis-hit areas, as reported in Aleppo, people are unable to go to the bakeries and queue up for bread due to insecurity. Instead, some intermediaries are supplying the bread at doorsteps at double price, which the poor and vulnerable farmers simply cannot afford.

Indebtedness among the rural families is on the rise, and the devaluation of the Syrian pound has put additional pressure on the small farmers and herders. Almost sixty percent of the households visited in Palmyra in Eastern Homs and Daar’a reported to have taken out loans from relatives, and some of them as high as sixty thousand Syrian pounds. In rural areas, where most of the people are at the subsistence level, thanks to the existing social fabric and system, borrowing exists at no interest rate. However, the irony is that since the situation of one family compared to another is not much different, no one is in a real good position to lend money to others. Furthermore, in some of the agriculture production areas, such as Daará and Rural Damascus, the local merchants and money lenders are lending money in US dollars only, and the medium-sized farmers with three to five hectares of land are entering into a vicious cycle of debt in hard currency. Since banking facilities and the provision of soft loans have been suspended at the moment, the small and medium-sized farmers are facing more difficulty accessing cash to meet the higher production costs.

Among the most vulnerable in the rural population, which accounts for about thirty percent of the rural population, five to ten percent is reported to be female-headed and is the most vulnerable. With little to no income and very little savings, high recurring expenses and many mouths to feed, their resources are fast depleting. The coping strategy for the small farmers and female-headed households is to cut the daily meals from three to two, stop eating meat, eat lower quality food, reduce the size of meals, buy less expensive food, buy food on credit, take children out of school, send children and young daughters to work, selling livestock and other assets, and cut back on medical and education expenses. Even the richest family in the village during a visit to Al Hassake reported to have food stock for only one more month.

Most of the vulnerable families visited across the country reported less income and more expenditure, and their life is becoming more difficult day by day. Some of the women interviewed confirmed to have sold their assets (including jewelries) to cope with the situation. One woman interviewed in Daará reported to have started begging in the street. Other women interviewed in Palmyra in Eastern Homs, Al Haasake, Al Raqqa and Aleppo confirmed the deterioration of their living conditions from beginning of this year and that their livelihood is just on the verge of collapse.

In some of the rural areas visted, seasonal migration of young boys and men to Lebanon and Saudi Arabia for work played an important role at the household level, especially for remittance. However, due to recent crisises in Lebanon and the danger of movement within Syria, people are afraid of moving out of their villages. A few families in Eastern Homs, mainly in the Al Badia region with the family size as big as seventeen, with almost no agriculture and very few heads of livestock, and largely dependent on remittance, feared a complete collapse of their livelihood system if the current situation continues for some time. A few families reported having their men still in Lebanon, but were unable to send any remittance due to unemployment there.

The Daará governorate alone that hosted nearly two hundred thousand migrant labors reported the return of nearly seventy percent of its labor force. Since most of this labor force originated from the northeastern and northern governorates, the mission observed additional stress on the natural resources and food demand in these areas with the return. With fewer income-generating opportunities for the returnee families, most of their savings have already been consumed. This has put extreme psychological pressure on these families, and some of them reported to be taking psychiatric medicines, which unfortunately was another financial burden for them. While visiting Al Hassake and Al Raqqa, the mission met some of these returnee families and found that these families are some of the most vulnerable ones. With no employment back in their native villages, large and extended families with almost no coping mechanism left reported that their livelihood was just on the verge of collapse.

The mission concludes that the farming and livestock-based livelihoods and household level food security of about thirty percent of the rural population and the internally displaced families currently living in the urban and semi-urban settings, which is about three million people,[1] faces a real threat and they need urgent assistance. For agriculture and livestock support, this totals to nearly 375,000 households. They are mainly subsistence farmers with less than 0.5 hectares of land, herders with less than thirty heads of livestock and internally displaced families living with their relatives or in rented houses in urban and semi-urban areas. Their household level food security situation is rapidly deteriorating and the coping strategy is also getting gradually diminished. These people need urgent food assistance as a life saving measure, and agriculture and livestock input assistance as life-sustaining intervention to restore their farming and livestock-based livelihoods. Particular attention needs to be given to the "returnee" migrant labors, female-headed households, small farmers, and small Bedouins and herders. Given the sense of urgency, this assistance is needed without any further delay. If the timely assistance is not provided, the livelihood system of these vulnerable people could simply collapse in few months time. Since the winter is approaching in few months time, urgent action is therefore necessary.

The following table represents the summary of damanges, losses and the overall short-term needs for the next twelve months.

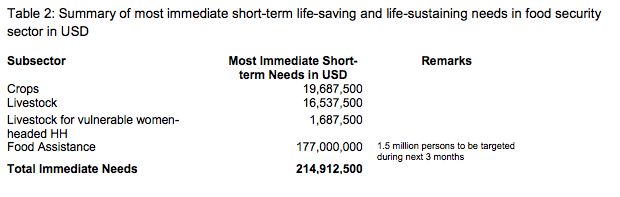

The following table presents the summary of most immediate short-term life-saving and life-sustaining needs in US Dollars for the next 3 to 6 months to be provided to the most vulnerable families.

--------------

NOTES

[1] This caseload figure is estimated based on the total population of about twenty million in the most affected nine governorates of Daará, Rural Damascus, Homs, Hama, Idleb, Aleppo, Al Raqqa, Deir Ezzor and Al Hassake with forty-six percent of the population living in rural areas, out of which thirty percent are considered as the most vulnerable rural farming and herder families. An additional caseload of around three hundred thousand people is estimated in urban and semi-urban areas displaced from the crisis-affected areas around the country based on the consultations carried out in the governorates.

[Click here to download the full report.]